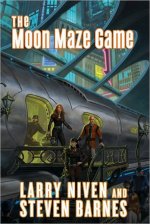

| The Moon Maze Game | ||||||||

| Larry Niven and Steven Barnes | ||||||||

| Tor, 364 pages | ||||||||

|

A review by Dave Truesdale

Dream Park was set in 2051 and featured a South Seas Treasure theme. The central plotline involved a

murder, some proprietary research material stolen, and the revelation that it was someone "inside" the game

who was the culprit.

1989's followup, The Barsoom Project, showcased an Inuit mythology theme as the live-action fantasy

RPG (where -- believe it or not -- gamers paid big bucks to lose weight via the game's obstacles), but tossed

into the mix Muslim terrorists (backed by a shady Muslim capitalist!) attempting to thwart the implementation

of a space elevator at the Park, from which the title is derived.

The California Voodoo Game (1992) had as its theme, as the title states, voodoo, and again murder.

Which brings us to The Moon Maze Game (2011), now set in 2085, 34 years following the amusement park's

debut. The corporation funding Dream Park (and authors Niven & Barnes) have now moved the action to the Moon,

as the finishing touches are being put on the new park located at Heinlein base. The basic setup of the game

is the same as in the previous novels: the elite live-action players from around the world flock to this

first-ever game set on the Moon, and the stakes for everyone are enormous. Potential players pay an exorbitant

entry fee, are winnowed out through exhaustive live-action exercises until only the number required for the

game remain. The corporation records everything for later edited broadcast to the world and the mega-bucks

they earn in return are massive. The winning player acquires immense prestige and respect on the now extensive

gaming tournament circuit (known as the IFGS, the International Fantasy Gaming Society), not to mention

monetary offers to appear in other games on Earth, or as highly paid consultants or designers. This is to

be the biggest, most prestigious, most anticipated Dream Park game in history -- and the first-ever on the Moon,

whose interests lie in attracting more tourists and business to its economy -- and its struggling bid for

independence (which is another nod to Heinlein and his 1966 Hugo award-winning novel The Moon is a Harsh Mistress).

With this backdrop -- and as in the previous books -- we are then given the fly in the ointment. Scotty

Griffin -- son of Alex Griffin, one of the original Dream Park characters -- is enlisted as

bodyguard (a.k.a. "Protection Specialist") to Ali Kikaya, teenaged son of the leader of a small, despotic African

nation, the Republic of Kikaya. Ali is ostensibly traveling to the Moon on vacation, but under false pretenses

and an alias becomes one of the select few winning their way into the game (he is an enthusiastic "home" gamer,

which has fueled his subterfuge). It is his attempted kidnapping by Kikayan rebels during the game that sets the

plot wheels in motion.

The second novel borrowed its title from Edgar Rice Burroughs' novels of Mars, whom the inhabitants of the

red planet called Barsoom. This time around the game's theme is derived from H.G. Wells' 1901 novel

The First Men in the Moon, as conceived by the game's chief designer, Xavier, who maintains total,

live-action control over the game's traps, puzzles, and other ingeniously conceived dangers. A sub-plot

develops when the Chief Operations Officer, Kendra Griffin, Scotty Griffin's ex-wife, is caught in the

middle between Scotty and Xavier, who once both sought her attentions in a heated rivalry during their

collegiate years as up-and-coming prodigies. Through a tragic bit of misfortune, Scotty has vowed never

to leave Earth again, which led to his divorce from Kendra. But now Scotty has returned and the old

rivalry between he and Xavier is once again in play, as Xavier can easily manipulate Scotty's

being "killed" in the game at any point, for Xavier also blames Scotty for falsifying information against

him in a scandal from years ago which has cost Xavier dearly in his subsequent career.

But when the terrorists discover that young Ali Kikaya is a player in the game and will stop at nothing to

kidnap him to further their political agenda, Xavier must re-evaluate his personal animus toward Scotty

(not to mention financial considerations for the corporation if the game is to be broadcast to the world

in the midst of a hostage crisis), and with the help of Kendra and others aid Scotty, Ali, and the other

gamers (without real weapons) to negotiate the deadly traps and defeat the terrorists before they are

killed. But it's not as easy as it may sound, for the terrorists have disabled all but a fraction of

the game's internal communications and functions, making help for the good guys a real life-and-death

problem, as the bizarre landscapes and monstrous, deadly life forms Xavier has created for the game from

Wells' novel must be worked around (or not) by both the terrorists and the gamers on their own, never

knowing what will come next. And if one of them, or a terrorist, inadvertently makes a wrong move, an

ill-advised shortcut to freedom or to the kidnapping of Ali, the entire dome may explode, sucking the

air supply into space and killing everyone. Only their experience as resourceful gamers and a knowledge

of Wells' story give Scotty and crew any margin, any hope for success, as Niven & Barnes toss in one

complication after another to be overcome, in tried-and-true adventure-thriller fashion. It's a wild ride.

On this immediate, immersed-in-the-story-as-it-unfolds level, all of this keeps the reader turning pages,

which is a good thing. But when one stands back it is easy to see that this is much the same basic formula

as previous installments but now merely moved to the Moon, with the basic theme based on Wells' Moon,

instead of voodoo, South Seas Treasure or Inuit mythology. It would seem to be a winning formula, that

of re-arranging the deck chairs and giving them a new coat of paint. The fear is that long-time

followers of the series will notice this quickly, and unless they find the paint on the chairs fresh

enough (which some very well may), might feel like they've been here before and come away a bit let down.

For newcomers The Moon Maze Game is recommended as a paperback purchase, an entertaining few hours of

escape into lively territory the reader may not have encountered before -- a perfect fit for a lazy summer

afternoon's reading pleasure.

For long-time Dream Park fans and especially the gamers among you, also a paperback recommendation, though

some might disagree with any recommendation, deciding to reignite the complaint voiced in response to

previous books of the balance between character development and game action. It is my view that in this

sort of fast-paced, Idea-action/adventure-thriller novel all that is needed by way of "character

development" is a sense of who the characters are, the rudiments of their individual back stories, and a

human conflict (or other personal relationship or entanglement -- be it of the conflictive or attractive

sort -- between or among these primary characters with which the reader may identify) or pro forma love

interest, for the setting, plot, and action are front stage and are what essentially drive the story. In

this, The Moon Maze Game succeeds. Some prefer more character development in their Dream Park

novels while some prefer more game action. It's an author's eternal dilemma, for no matter how hard they try

they just can't please everyone it seems. Everyone's a critic.

Dave Truesdale has edited Tangent and now Tangent Online since 1993. It has been nominated for the Hugo Award four times, and the World Fantasy Award once. A former editor of the Bulletin of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, he also served as a World Fantasy Award judge in 1998, and for several years wrote an original online column for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. | |||||||

|

|

If you find any errors, typos or other stuff worth mentioning,

please send it to editor@sfsite.com.

Copyright © 1996-2014 SF Site All Rights Reserved Worldwide